In the coming years, a vaccine against tick-borne Lyme disease developed by Pfizer may enter the pharmaceutical market. Meanwhile, research continues at the Latvian Biomedical Research and Study Centre that could lead to even more effective vaccines against this disease.

Lyme disease, caused by the bacterium Borrelia, is the most common tick-borne infection in the Northern Hemisphere. It affects more than 14 percent of the world’s population. According to data from the Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (SPKC), more than 500 cases were detected in Latvia last year, twice as many as in 2023. If left untreated, Lyme disease can cause joint pain, heart palpitations, and other health problems.

Leading researcher Kalvis Brangulis from the Biomedical Research Centre explains that as many as 130 different protein types can be found on the surface of Borrelia. Some of these proteins could be the most effective components of a vaccine, as they are the first to interact with the host and can trigger antibody production against Lyme disease.

"This means they are the ones recognised by the host organism, for example, the human body. The body then produces antibodies against them. That is why it is logical to study surface proteins and determine whether they can be used as vaccine antigens. For example, the protein I studied, CspZ, is one of those. It is located on the surface; this was experimentally confirmed, and it was interesting to determine whether it could be used for a vaccine," Brangulis explained.

The protein CspZ, which the researcher has studied most extensively, helps the bacteria evade attack by the human immune system. The vaccine currently being developed by Pfizer, on the other hand, is based on a different Borrelia surface protein discovered at the end of the last century. The first vaccines were also developed at that time, although they were available for only a few years. Concerns about their safety arose, but they later proved unfounded. The vaccine now under development is based on the same protein, though slightly modified, making it improved.

Brangulis has also sought to improve the CspZ protein he studies, making it more useful for antibody production. The protein must be stabilised by slightly altering its structure to ensure that it functions as expected in a vaccine.

"This is called structural vaccinology, and in fact, it is becoming quite a popular field, where modifications are made in this way to improve the protein structure," the researcher noted.

With Pfizer’s upcoming vaccine, three booster doses may be required to achieve immunity. However, if a vaccine were developed using the protein studied by Brangulis, no more than two doses might be needed. At least that is what data from collaboration partners in the United States suggest, based on experiments with antibodies derived from the CspZ protein tested in mice.

"That shows the protein truly has the potential to be better than what is currently being developed," Brangulis said.

Before understanding what this protein looks like, however, it was necessary to determine its three-dimensional structure.

"To do that with a protein is complicated. You cannot simply look at it under a light microscope because it is too small to be seen that way. Instead, you need to use X-rays. But to use X-rays, you first need to obtain crystals of the protein."

Once the crystals are formed, they are frozen in liquid nitrogen and sent to a foreign research institute where a synchrotron is available, a particle accelerator in which electrons move at nearly the speed of light, producing very powerful X-rays that help determine the overall protein structure.

One of the most time-consuming processes in the researcher’s work is obtaining the proteins. They are grown in bacteria and then purified from other proteins not needed for the study to obtain pure Borrelia protein.

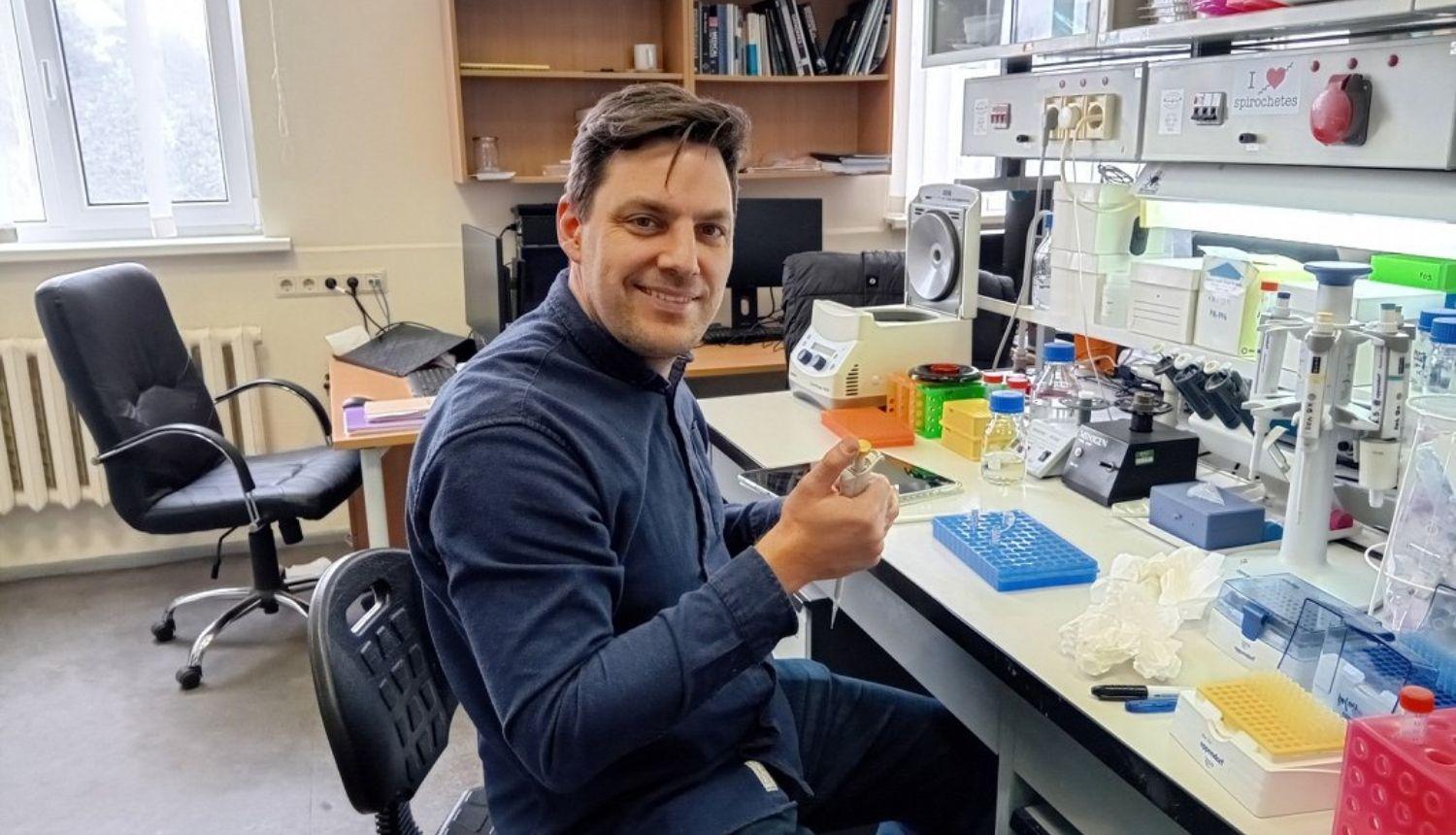

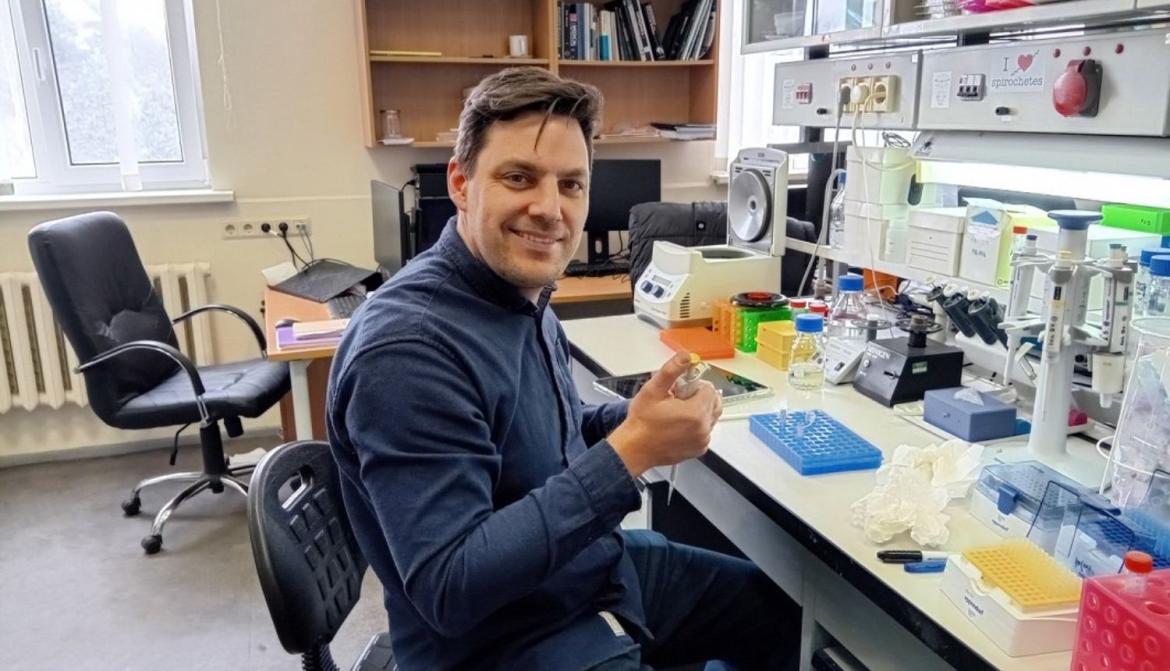

During the interview, the researcher continued working, placing protein-containing tubes into a specialised centrifuge. He explained:

"These tubes have a membrane that allows everything smaller than a certain size to pass through. I know my protein is larger, so it cannot pass through the membrane. When I centrifuge it, the solution flows through, but my protein remains. As a result, it becomes more concentrated."

The centrifuge is the final stage in purifying and concentrating the protein. Before that, the researcher had already purified it using chromatography.

Brangulis has been working in this field for more than 15 years. The first structure of a Borrelia protein was obtained in 2010. On average, determining the structure of one such protein takes about a year, but Brangulis has already obtained 60 Borrelia protein structures and plans to continue his research.