For decades, people living with myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), have found themselves in a strange and painful grey zone between illness and disbelief. They feel profoundly unwell, yet are repeatedly told that nothing is wrong. Many have lost careers, relationships, financial security, and often their sense of identity, while the medical system has struggled to decide whether their disease even exists.

Today, the situation is beginning to change. The emergence of long COVID has forced medicine to confront a reality that ME/CFS patients have known for generations: viral infections can trigger a long-lasting, multisystem disease with devastating consequences.

This article presents the perspective of a patient advocate on a long-misunderstood condition, myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome). It explores the research currently being conducted at the Institute of Microbiology and Virology within the Science Centre at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU).

One of the authors of this article is Paul, a person living with ME/CFS who supports others affected by the illness. The article examines why the disease has been misunderstood, how long COVID has transformed the field, and how new research, including studies currently underway at RSU’s Institute of Microbiology and Virology in Riga, is reshaping our understanding of this infection-associated condition.

Why Has This Disease Been So Difficult to Understand?

ME/CFS has a long history. Outbreaks of similar illnesses were reported as early as the 1930s and 1950s, often following viral infections and affecting entire communities. Patients reported profound fatigue, muscle pain, neurological symptoms, and immune disturbances. Most characteristically, all of these symptoms worsened even after minimal physical or mental exertion.

Despite this history, clinicians struggled to classify the disease because it did not fit neatly within existing medical specialities.

Standard blood tests were often described as “normal,” and conventional imaging studies typically revealed little. When objective abnormalities were detected, they were frequently dismissed as incidental or unrelated, rather than recognised as manifestations of a single underlying disease.

Language played a significant role in public misunderstanding. In the United States, the term “chronic fatigue syndrome” came into medical use in the early 1990s. Unintentionally, the name encouraged a narrow and trivial interpretation of a complex disease.

In the United Kingdom, this uncertainty proved especially damaging. Influential clinical and policy guidelines increasingly framed the illness as a consequence of deconditioning and maladaptive beliefs rather than as a persistent post-infectious condition. This approach promoted graded exercise therapy, the idea that patients should gradually increase physical activity to recover.

For people with ME/CFS, whose hallmark symptom is deterioration after exertion, such approaches often caused serious and long-lasting harm. Many patients experienced significant worsening; some became housebound or bedbound.

The original name, myalgic encephalomyelitis, implies inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. Its replacement, chronic fatigue syndrome, trivialised the disease and reduced it to a symptom that everyone experiences from time to time. Yet fatigue is not the definition of ME/CFS.

Growing evidence suggests that the illness reflects a failure to fully resolve the biological changes that normally occur during an acute viral infection.

Instead of returning to baseline, key systems, including cellular energy metabolism, immune regulation, cardiovascular function, and brain signalling, remain disrupted.

These unresolved abnormalities interact, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of immune activation, impaired cellular energy production, vascular dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and pain. The result is a chronic, whole-body disease in which even minor physical or cognitive exertion can trigger disproportionate and prolonged deterioration.

A Society That Values Vitality and Punishes Its Loss

Modern society prizes energy, productivity, resilience, and recovery. People with ME/CFS stand in direct contrast to this cultural ideal. Feeling tired after effort is acceptable; being unable to recover is not.

The disease strips individuals of stamina, clarity of thought, and physical capacity, often at an age when careers and families are still being built. Because the loss of function is largely invisible, patients are frequently perceived as lazy, unmotivated, or unwilling to help themselves.

The illness’s unusual complexity deepens the problem. ME/CFS involves multiple interacting organ systems, and investigation of its underlying mechanisms has only recently gained momentum. Patients often struggle to explain what is happening to them in ways that family or friends can easily understand. When symptoms fluctuate, or when exertion triggers delayed rather than immediate deterioration, the disease may appear inconsistent or even contradictory to observers.

The communication gap widens due to the powerful societal assumption that medical authority is beyond question. In most diseases, such trust is justified. However, in ME/CFS, decades of incomplete understanding and flawed theories have meant that patients themselves have often become the most informed individuals on the subject.

When doctors express uncertainty, scepticism, or dismissal, that attitude can be adopted by families, employers, and institutions, leaving patients isolated not only by symptoms but by disbelief. A cruel situation emerges: severely ill people must defend the legitimacy of their illness, sometimes even among their closest circle.

I/CFS itself does not cause the resulting psychological burden, but rather by living with a disease that society does not understand.

Like the illness, the assumption that “the doctor knows best” has disproportionately affected women. Diseases that predominantly affect women, especially those without a single visible pathology, have historically been attributed to emotional, psychological, or social causes. In a profession long dominated by men in leadership and research priorities, women’s reports of pain, exhaustion, and functional loss have too often been reframed rather than investigated.

In ME/CFS, bias collided with scientific uncertainty, creating a perfect storm: a complex post-infectious illness affecting mostly women, lacking a simple diagnostic test, and therefore easy to dismiss.

How Long COVID Changed Everything

The COVID-19 pandemic transformed the landscape almost overnight. Millions of previously healthy people developed persistent symptoms after acute infection: exhaustion, cognitive dysfunction, autonomic disturbances, pain, and exercise intolerance. Many found that exertion did not improve their condition; it worsened it.

For ME/CFS patients, long COVID felt strikingly familiar; the symptoms overlapped almost exactly. What changed was scale and visibility.

When millions, including healthcare professionals, experienced post-viral disability, older psychological explanations lost credibility.

Long COVID demonstrated that post-acute infection syndromes are biological, systemic, and potentially long-lasting.

It also created unprecedented opportunities: increased research funding, international collaboration, and willingness to revisit entrenched assumptions. ME/CFS was no longer an anomaly but part of a broader context.

It became evident that some individuals do not fully recover after infection. Systems responsible for immune regulation, energy metabolism, blood flow, and brain function remain dysregulated. In some, this unresolved post-infectious biology evolves into a chronic condition indistinguishable from ME/CFS, characterised by post-exertional symptom exacerbation, cognitive impairment, autonomic instability, and chronic pain.

Long COVID not only validated decades of ME/CFS patient experience but also revealed a broader group of post-acute infection syndromes, conditions in which recovery fails and individuals become trapped in a self-sustaining cycle of inflammation, impaired energy production, and neurological stress.

Asking the Right Questions

Behind every scientific debate lies a human story. ME/CFS and long COVID can dismantle lives with brutal efficiency. People lose their jobs because they cannot maintain the required working hours. Relationships collapse under the strain of misunderstanding. Financial hardship is common, particularly where disability support systems fail to recognise disease severity.

For the most severely affected, ME/CFS can be catastrophic. Some cannot tolerate light, sound, or touch. Some are entirely bedbound, fed by tube, and dependent on others for basic care.

In rare but documented cases, individuals have died from direct or indirect consequences of the disease, including deaths associated with prolonged suffering and, in some instances, suicide. These cases are often absent from public discussion, yet they underscore why research matters and why patients fight so hard to be heard.

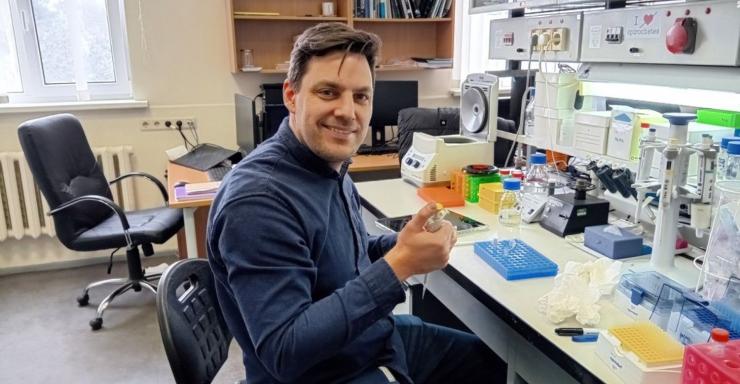

Research into ME/CFS has been underway at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU) for a long time. In this context, the work of the newly established research group, known as “Prusty Lab,” marks a turning point. Rather than asking whether ME/CFS is “real,” the research asks: how do viral infections leave a lasting biological imprint on the body?

A central focus is mitochondria, the structures within cells that regulate energy production, immune signalling, and cellular stress responses. Researchers at the Institute of Microbiology and Virology at RSU’s Science Centre have demonstrated that factors present in the blood of ME/CFS and long COVID patients can disrupt the structure and function of mitochondria in healthy cells. This suggests that circulating biological signals actively sustain the disease.

One striking finding is elevated fibronectin, a protein involved in tissue repair and vascular function, along with significantly altered immunoglobulin (antibody) profiles.

These findings indicate that the body may be trapped in a maladaptive repair and immune state, as though the signals of acute infection were never fully switched off.

Taken together, the research supports a new understanding of ME/CFS and long COVID as unresolved post-viral physiological disturbances. Immune dysregulation, vascular dysfunction, mitochondrial impairment, and altered brain signalling interact to create a self-reinforcing cycle of chronic inflammation, pain, and energy depletion.

Crucially, these are measurable biological changes. They offer a plausible mechanism linking viral infection, immune disturbance, impaired energy metabolism, and the widespread symptoms experienced by patients. For many in the ME/CFS community, this research has provided something long denied, validation grounded in molecular biology.

Genetics and Future Directions

Recent advances in genetics have added another important layer. Large-scale studies suggest that some individuals carry gene variants that influence immune responses, metabolic regulation, and cellular stress responses. This does not mean ME/CFS is purely genetic. Rather, it points to biological susceptibility, a vulnerability that may remain hidden until triggered by infection or other stressors.

This helps explain why the same virus leaves one person unaffected while causing chronic illness in another.

The future of ME/CFS research is becoming more coherent. The goal is no longer to help patients adapt to illness, but to identify biological subtypes, develop objective diagnostic tests, and target underlying mechanisms.

Blood biomarkers, immune signatures, and metabolic profiles are currently under investigation. Treatment is likely to evolve step by step: therapies that stabilise immune dysfunction, support mitochondrial function, or interrupt infection-driven pathological feedback loops. Progress will not be immediate, but for the first time in decades, it is moving in the right direction.

About the Authors

Bhupesh Kumar Prusty is a tenured professor at Rīga Stradiņš University with over 25 years of experience in chronic viral diseases.

Paul Watton is 62 years old and has lived with ME/CFS for more than 20 years. Now retired, he previously worked as a project manager in the construction industry. He lives in the United Kingdom with his wife Deb, to whom he has been married for over 40 years. They met while studying at the University of Manchester. They have three adult children, the youngest of whom is a surgeon. Paul’s family history includes autoimmune and connective tissue diseases.